Horus of Egypt, son of a human virgin and a god.

I’ve often wondered whether we have done Jesus a great disservice by assigning him the same birthday as ancient gods. In mythology, Horus of Egypt (c. 3000 BC), Mithra of Persia (c. 1200 BC), Attis of Greece (c. 1200 BC), Krishna of India (c. 900 BC), Dionysus of Greece (c. 500 BC) and others were “born” on December 25.

All are the alleged offspring of virgin mothers and powerful gods. As legend has it, these illustrious demigods healed the sick, raised the dead, and were murdered by the establishment. Each one was resurrected after three days.

While it’s possible that December 25 was Jesus’s birthday, no one can pinpoint anything, anywhere that cites that date or justifies claims that he is “the reason for the season.”

Despite that, hundreds of songs have been written, thousands of pageants have been performed, and millions of gifts have been exchanged on December 25th. The Pope’s latest book says our Christmas traditions are based on myth. If you want the Cliff notes version, Yahoo! News outlines “Five Surprising Facts about Christmas” in this post.

How many times was Jesus born?

Many contend that to be a Christian, you must absolutely positively believe the Bible’s accounts of Jesus’s birth and death. Fair enough, since religion typically requires unquestioning belief. But which accounts are we required to believe: Luke’s or Matthew’s? (Were you brave enough to take the poll in my previous post, Manger or Mary’s House?)

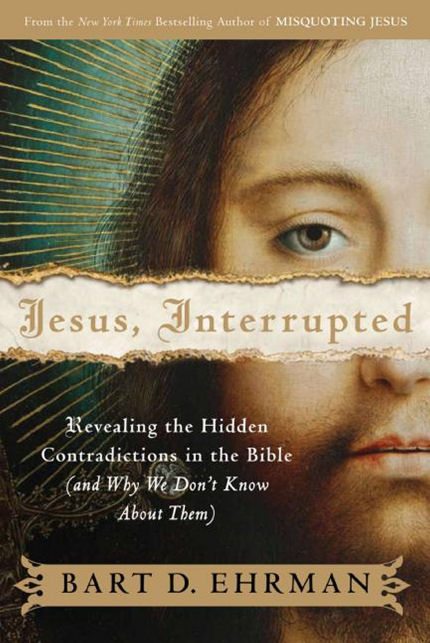

As discussed in that post, most of us haven’t noticed that the Bible cites two different locations for Jesus’s birth. Bible scholar Bart D. Ehrman says it’s because we read the Bible as we read other books: vertically, from the top of the page to the bottom, when it’s often more insightful to read it side-by-side.

To help his students glean more from the text, Ehrman asks them to list all the facts in a Bible story, then compare them with facts stated elsewhere. It’s a technique also used by the Rev. Gaylon McDowell, my New Testament teacher at Christ Universal Temple.

What I discovered when I did that exercise is that both narratives began and ended the same, but nothing else matched:

If you’re interesting in learning and growing, I’d suggest that you try this technique with the Bible’s accounts of Jesus’s death and the days that followed. I think you’ll find it as insightful as the fact that the Book of James, written by Jesus’s brother, contains neither of these accounts.

How we missed it the first time

More fascinating, try this technique with the Great Flood story in Genesis, which claims that God couldn’t think of a better solution for man’s wickedness than to kill every living thing—including innocent infants, animals, fish and fauna. According to Bible and Torah scholars, five flood myths were woven together to Genesis. Because of that, you’ll need more than two columns on your page because the “facts” frequently contradict each other from one verse to another, not simply from one chapter or book to another.

Because we are told that the Bible is the inerrant “Word of God,” we typically dismiss or ignore inconsistencies. In other books, we’d consider it implausible for someone to be born in two different places. We’d easily notice that facts are changing from one sentence (or verse) to another.

With the Bible, we negotiate and reconcile blatant contradictions. That’s why we often see the star in Matthew’s story positioned over the stable and shepherds in Luke’s story. The wise men, who went to the house, are curiously standing near the shepherds and manger.

Why the facts don’t line up

Many believe the gospels were written by Jesus’s disciples. But based on the dates their gospels were written, Bible scholars agree that neither Matthew nor Luke ever met Jesus. They also note that the Book of James, written by Jesus’s brother, doesn’t mention the miraculous virgin birth involving his very own mother.

Matthew and Luke, however, were fervently committed to converting more followers to Judaism’s new sect, Christianity. Matthew crafted his birth narrative to attract more Jews by including as many elements as possible to link Jesus to the Jewish prophesies about the Messiah. In particular, it was important to establish that he was born in Bethlehem and from the lineage of King David. For good measure, he drew a parallel to Moses, who escaped the Pharoah’s mandate to kill newborn boys.

Luke’s aim was to convert everybody, Jew and Gentile. His birth narrative used imagery of common folk, shepherds, who rejoiced at the birth of the Messiah.

Both men realized that they needed a device to get Jesus to Nazareth after the birth. After all, he was known as Jesus of Nazareth, not Jesus of Bethlehem.

Does myth matter?

Completely lost in these tangled fables is the real significance of Jesus’s life: His message for us to love unconditionally and forgive untiringly, as exemplified by the father in the Prodigal Son parable. Another casualty: His admonitions for us to avoid judging and condemning each other.

If Jesus’s mission was to teach us that we are one with the father and to save us from committing sin by loving, forgiving and being nonjudgmental, have we belittled that mission by dedicating ourselves instead to errant words, unrelated traditions and worshiping the life story of mythical gods? If we haven’t honored Jesus’s teachings, as urged in his brother James’ book, what on Earth are we celebrating?

Plus, as Ehrman pointed out in his latest book. “Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them),” we tend to read the Bible vertically, from the top of the page to the bottom—the same way we read other books. And that could be a problem.

Plus, as Ehrman pointed out in his latest book. “Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them),” we tend to read the Bible vertically, from the top of the page to the bottom—the same way we read other books. And that could be a problem.